Jayne O’Donnell and David Robinson, USA TODAY NETWORK, Published 11:11 a.m. ET Feb. 28, 2019

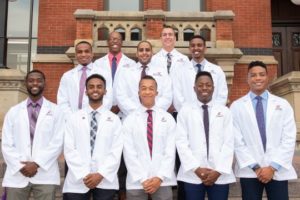

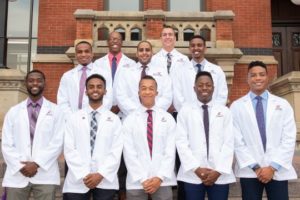

These are the 10 black men in University of Cincinnati College of Medicine’s first year class at their “White Coat Ceremony,” (Photo: Colleen Kelley/University of Cincinnati)

WASHINGTON – Gabriel Felix is on track to graduate from Howard University’s medical school in May.

The 27-year-old from Rockland County, N.Y., has beaten the odds to make it this far, and knows he faces challenges going forward.

He and other black medical school students have grown used to dealing with doctors’ doubts about their abilities, and other slights: being confused with hospital support staff, or being advised to pick a nickname because their actual names would be too difficult to pronounce.

“We’re still on a steady hill toward progress,” says Felix, president of the Student National Medical Association, which represents medical students of color. But “there’s still a lot more work to do.”

After decades of effort to increase the ranks of African-American doctors, blacks remain an underrepresented minority in the nation’s medical schools.

USA TODAY examined medical school enrollment after the wide coverage of the racially controversial photo that appeared in the 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook entry of Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam. The picture showed one person in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan hood and robe.

The proportion of medical students who identified as African-American or black rose from 5.6 percent in 1980 to 7.7 percent in 2016, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. That’s a substantial increase but still short of the 13.2 percent in the general population.

The disparity matters, physicians, students and others say, because doctors of color can help the African-American community overcome a historical mistrust of the medical system – a factor in poorer health outcomes for black Americans.

“It’s been a persistent, stubborn racial disparity in the medical workforce,” says Dr. Vanessa Gamble, a professor at George Washington University. “Medical schools have tried, but it also has to do with societal issues about what happens to a lot of kids in our country these days.”

Those who have studied the disparity blame much of it on socioeconomic conditions, themselves the legacy of systemic racism. African Americans lag other Americans in household income and educational opportunity, among other indicators.

Medical schools and professional organizations have tried to boost enrollment and graduation rates by considering applicants’ socioeconomic backgrounds when reviewing grades and test scores, connecting doctors of color with elementary and middle schools and awarding more scholarship money.

They’ve achieved some success: The number of medical students who identified as African-American or black grew from 3,722 in 1980 to 6,758 in 2016, an 82 percent increase.

Individual schools have outperformed their peers.

Eastern Virginia Medical School has increased the enrollment of students of color since then. In 1984, 5 percent of M.D. students identified as black, the only category then available. In the school’s most recent class, 12.4 percent identified as African, African-American, Afro-Caribbean or black.

But further progress toward a more representative student body nationwide remains elusive. That’s due largely to the high cost of medical school – student loans average $160,000 and can take decades to pay off – and the attraction of other professional options available to the strongest minority students that cost less and require fewer years of training.

The benefits of greater enrollment could be considerable: Studies show that having more black doctors would likely improve black health in the United States. Many African-Americans remain mistrustful of the health care system, with some historic justification, and so are less likely than others to seek preventative or other care.

Gamble knows the phenomenon as well as anyone. She chaired a committee that investigated the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the notorious experiment conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972. Researchers withheld treatment from a group of black men with syphilis to study the progress of the disease, jeopardizing their health and that of their sexual partners.

Building pipelines to medical school

Universities are working to boost minority enrollment and increase the likelihood that students will stay in school and pass the exams required to graduate and get licensed to practice.

Dr. Thomas Madejski is president of the Medical Society of the State of New York. (Photo: Medical Society of the State of New York)

Dr. Thomas Madejski is president of the Medical Society of the State of New York. (Photo: Medical Society of the State of New York)

Dr. Thomas Madejski, president of the Medical Society of the State of New York, says efforts such as the American Medical Association’s Doctors Back to School program, in which physicians of color visit grade schools, help encourage minority students consider careers in medicine.

But he cautions that such programs don’t address all of the socioeconomic hurdles confronting African Americans.

“I think we may have to relook at some of the factors that may still be barriers and create some new initiatives to overcome those and get the citizens of the U.S. to have the physician workforce that they want and need,” Madejski says.

His group and others are pushing for tuition relief and expansion of scholarship programs for underrepresented groups.

Gabriel Felix is a fourth year student at Howard University’s medical school and president of the Student National Medical Association. (Photo: Courtesy of Gabriel Felix)

Gabriel Felix is a fourth year student at Howard University’s medical school and president of the Student National Medical Association. (Photo: Courtesy of Gabriel Felix)

Felix, the Howard student, calls for more outreach by physicians of color, particularly in African American communities.

Felix’s parents are from Haiti, where black doctors are a common sight. They could easily envision the career for their son. African-American parents, however, might not encourage their children as much, Felix says.

Dr. Mia Mallory is associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of Cincinnati medical school.

“Patients do better when they are taken care of by people who look like them,” she says. “So we’re trying to grow talented physicians that look like them and are more likely to go back into the community they came from.”

Dr. Mia Mallory is associate dean in the office of diversity and inclusion and an associate professor in pediatrics at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. (Photo: University of Cincinnati College of Medicine)

Dr. Mia Mallory is associate dean in the office of diversity and inclusion and an associate professor in pediatrics at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. (Photo: University of Cincinnati College of Medicine)

Some of what’s being done:

► New York. About a third of the state’s population is black and/or Latino, but only 12 percent of doctors in practice are. The decision of New York University’s decision to offer free tuition to medical students who maintain a certain grade point average has more than doubled the number of applicants who identify as a member of a group that’s underrepresented in medicine.

Associated Medical Schools of New York, which represents the state’s 16 public and private medical schools, says several programs give college students academic help, mentoring or other aid, and guarantee medical school acceptance upon completion.

About 500 practicing physicians from underrepresented groups graduated from one of these programs at University at Buffalo.

These were “kids who otherwise never would have gotten into medical school,” says Jo Wiederhorn, president of Associated Medical Schools of New York.

The share of black and Latino students at medical school rose from 13.5 percent in the 2010-11 school year to 15.4 percent for the past school year, Wiederhorn said.

► Maryland. University of Maryland, Baltimore County, produces more African-Americans who go on to earn dual M.D./Ph.D. degrees than any college in the country.

Its Meyerhoff Scholars program selects promising high school students for a rigorous undergraduate program that connects them with research opportunities, conferences, paid internships, and study-abroad experiences. The program is open to all people, but nearly 70 percent of the scholars are black.

The university also sends students in its Sherman Scholars program to teach math and science in disadvantaged elementary schools in the Baltimore area. That helps build an early pipeline to the university and its science and math programs.

UMBC President Freeman A. Hrabowski III says, “We’re going to find some prejudice wherever we go.” But he prefers to look for solutions that keep students of color in math and science, which increases their chances of medical school acceptance.

► University of Cincinnati. The College of Medicine welcomed the largest group of African-American men in its history last year at 10 – an important milestone, given the gender gap within the few black doctors.

Mallory says the school looks at students’ applications “holistically,” considering “what it took for them to get where they are.” That includes whether they had to work while they were in college and whether they had access to tutors.

The school’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion hired Dr. Swati Pandya, a physician and learning specialist, to teach medical school students how to take standardized tests and improve study habits.

All of the school’s third-year students last year passed the first of their medical licensing exams, achieving the highest average in the school’s and the highest of any medical school in the state.

Why so few?

Dr. Georges Benjamin executive director of the American Public Health Association, cites the criminal justice system’s targeting of young black men and the pull of other professions for others.

“The cream of the crop has a broader portfolio of things they can do,” Benjamin says. “They can go into other disciplines, including MBA and law programs.”

Dr. Garth Graham is a cardiologist by training, but in a nearly 20-year career, he has become something akin to a doctor of disparities.

A former assistant secretary in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health, he’s Aetna’s vice president of community health and president of the Aetna Foundation.

He also chairs the Harvard Medical School Diversity Fund, which supports science, technology, engineering and math education and other support for minority students and faculty members in kindergarten through grade 12.

The National Bureau of Economic Research studied African-American men’s use of preventive health services when they had black and non-black doctors. The bureau reported last year that black doctors could reduce black men’s deaths from heart disease by 16 deaths per 100,000 every year. That would reduce the gap between black and white men by 19 percent.

Black doctors “bring a cultural understanding because of their background in their communities,” Graham says. “Relatability is important in patient-doctor relationships.”

Contributing: Shari Rudavsky, The Indianapolis Star

Read the article online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2019/02/28/medical-school-student-african-american-enrollment-black-doctors-health-disparity/2841925002/

Dr. Thomas Madejski is president of the Medical Society of the State of New York.

Dr. Thomas Madejski is president of the Medical Society of the State of New York.  Gabriel Felix is a fourth year student at Howard University’s medical school and president of the Student National Medical Association.

Gabriel Felix is a fourth year student at Howard University’s medical school and president of the Student National Medical Association.  Dr. Mia Mallory is associate dean in the office of diversity and inclusion and an associate professor in pediatrics at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

Dr. Mia Mallory is associate dean in the office of diversity and inclusion and an associate professor in pediatrics at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

Natasha was born and raised in the Bronx, NY and witnessed “health disparities” long before she was old enough to understand the term. During a leave of absence in her undergraduate career, Natasha served with AmeriCorps at a federally qualified health center in the South Bronx. That experience inspired her to return to the health center after graduation to implement various quality improvement projects with the goal to help make the Bronx a healthier place. Natasha subsequently pursued a Master’s in Public Health from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and worked diligently to get into medical school through the AMSNY Post-Baccalaureate Program. As a physician, she wants to serve disadvantaged and Latino populations within an urban setting. Natasha plans to pursue a residency in primary care and to work with underserved communities improving preventative care.

Natasha was born and raised in the Bronx, NY and witnessed “health disparities” long before she was old enough to understand the term. During a leave of absence in her undergraduate career, Natasha served with AmeriCorps at a federally qualified health center in the South Bronx. That experience inspired her to return to the health center after graduation to implement various quality improvement projects with the goal to help make the Bronx a healthier place. Natasha subsequently pursued a Master’s in Public Health from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and worked diligently to get into medical school through the AMSNY Post-Baccalaureate Program. As a physician, she wants to serve disadvantaged and Latino populations within an urban setting. Natasha plans to pursue a residency in primary care and to work with underserved communities improving preventative care. Karole was raised by her biological parents who were also foster parents to a number of children and believes that her diverse upbringing exposed her to the power of inclusion and the need for care. When she was in college, Karole’s father experienced long hospitalization after receiving an incorrect hernia repair which exposed Karole to the pitfalls in the healthcare system and which led to her interest in health disparities. Karole feels strongly that all individuals should receive quality treatment regardless of race, gender, disability, neighborhood or history of trauma. Karole intends to work in a publicly funded hospital after completing her training and return to serve the disenfranchised communities that sparked her interest.

Karole was raised by her biological parents who were also foster parents to a number of children and believes that her diverse upbringing exposed her to the power of inclusion and the need for care. When she was in college, Karole’s father experienced long hospitalization after receiving an incorrect hernia repair which exposed Karole to the pitfalls in the healthcare system and which led to her interest in health disparities. Karole feels strongly that all individuals should receive quality treatment regardless of race, gender, disability, neighborhood or history of trauma. Karole intends to work in a publicly funded hospital after completing her training and return to serve the disenfranchised communities that sparked her interest. Melissa was born in Brooklyn, New York, and was exposed to medicine through her pursuit of a career in forensics and law enforcement. Melissa took an undergraduate psychology course and then interned at the Medical Examiner’s Office of New York. While working there, she was mentored by the Chief of Staff and Director of Forensic Investigations and learned more about healthcare delivery which changed her path to medical school. As a graduate student, Melissa participated in research related to cardiovascular disease in Latina women of the Bronx and developed a passion for healthcare activism, social justice, and mentorship. Melissa is currently a fourth-year medical student and plans to do her residency in general surgery. She is looking forward to practicing as a female surgeon of color in Brooklyn.

Melissa was born in Brooklyn, New York, and was exposed to medicine through her pursuit of a career in forensics and law enforcement. Melissa took an undergraduate psychology course and then interned at the Medical Examiner’s Office of New York. While working there, she was mentored by the Chief of Staff and Director of Forensic Investigations and learned more about healthcare delivery which changed her path to medical school. As a graduate student, Melissa participated in research related to cardiovascular disease in Latina women of the Bronx and developed a passion for healthcare activism, social justice, and mentorship. Melissa is currently a fourth-year medical student and plans to do her residency in general surgery. She is looking forward to practicing as a female surgeon of color in Brooklyn. Bradley, a fourth-year student at Jacobs School of Medicine at the University at Buffalo, gained interested in becoming a physician when he was 10 years old, when a physician took the time to comfort him after delivering the news of his father’s tumor. With his sights on medical school, Bradley attended SUNY Oswego, where the director of the College Science Technology Entry Program (CSTEP) mentored him through the medical school application process. While in medical school, Bradley has volunteered extensively at the medical school’s drop-in clinic where free, routine healthcare and preventive services are provided to underserved and uninsured Buffalo residents, as well as planning and running community events. He is also heavily involved in the Student National Medical Association (SNMA) and their mentoring program for minority students called RX for Success.These experiences have solidified Bradley’s interest and commitment to working as a physician in an underserved area.

Bradley, a fourth-year student at Jacobs School of Medicine at the University at Buffalo, gained interested in becoming a physician when he was 10 years old, when a physician took the time to comfort him after delivering the news of his father’s tumor. With his sights on medical school, Bradley attended SUNY Oswego, where the director of the College Science Technology Entry Program (CSTEP) mentored him through the medical school application process. While in medical school, Bradley has volunteered extensively at the medical school’s drop-in clinic where free, routine healthcare and preventive services are provided to underserved and uninsured Buffalo residents, as well as planning and running community events. He is also heavily involved in the Student National Medical Association (SNMA) and their mentoring program for minority students called RX for Success.These experiences have solidified Bradley’s interest and commitment to working as a physician in an underserved area. Catherina was born in New York to Haitian immigrant parents who experienced financial hardships. Growing up, Catherina found a community through her church and was active in their community service activities, including distributing food at homeless shelters and playing the violin at a local senior center. Catherina also had hands-on experience with medicine while helping her mother take care of her grandmother who suffered from a number of chronic illnesses as well as a brain aneurism. Monitoring her grandmother’s medications and serving as a caregiver at such an early age sparked Catherina’s interest in becoming a physician, a goal which she has pursued to SUNY Downstate where she is a second-year student this fall. Catherina has worked as a medical scribe for an urgent care facility, giving her a firsthand look at the health disparities in New York. She looks forward to serving a disadvantaged community here when she is finished with her training.

Catherina was born in New York to Haitian immigrant parents who experienced financial hardships. Growing up, Catherina found a community through her church and was active in their community service activities, including distributing food at homeless shelters and playing the violin at a local senior center. Catherina also had hands-on experience with medicine while helping her mother take care of her grandmother who suffered from a number of chronic illnesses as well as a brain aneurism. Monitoring her grandmother’s medications and serving as a caregiver at such an early age sparked Catherina’s interest in becoming a physician, a goal which she has pursued to SUNY Downstate where she is a second-year student this fall. Catherina has worked as a medical scribe for an urgent care facility, giving her a firsthand look at the health disparities in New York. She looks forward to serving a disadvantaged community here when she is finished with her training. Zacharia was born in war-torn Somalia but was raised in a refugee camp in Kenya by his older sister for 12 years before gaining asylum in the United States. When Zacharia and his sister relocated to Syracuse, New York, he was unable to read, write, or speak English in addition to many other struggles as an immigrant. His passion for medicine grew from watching his older sister lose her eyesight and battle Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder stemming from her experiences in Somalia. After spending some years learning English, Zacharia was a translator for his sister and her healthcare staff which intensified his passion for medicine and for helping individuals in need. Zacharia is back in Syracuse for medical school in his second year at SUNY Upstate Medical University and looks forward to practicing in underserved communities, providing both medical care and empathy gained through his own personal experiences.

Zacharia was born in war-torn Somalia but was raised in a refugee camp in Kenya by his older sister for 12 years before gaining asylum in the United States. When Zacharia and his sister relocated to Syracuse, New York, he was unable to read, write, or speak English in addition to many other struggles as an immigrant. His passion for medicine grew from watching his older sister lose her eyesight and battle Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder stemming from her experiences in Somalia. After spending some years learning English, Zacharia was a translator for his sister and her healthcare staff which intensified his passion for medicine and for helping individuals in need. Zacharia is back in Syracuse for medical school in his second year at SUNY Upstate Medical University and looks forward to practicing in underserved communities, providing both medical care and empathy gained through his own personal experiences. Akya grew up in Brooklyn, New York, after her mother immigrated from Jamaica to secure better services for her son who is profoundly mentally disabled. Akya learned that while medical care was better in the United States, her mother and brother still struggled to access quality medicine and culturally competent care. This inequity led Akya to pursue a career in medicine but also drove her to serve vulnerable communities and individuals who are chronically underserved. After completing her post-bac degree at the AMSNY University at Buffalo program, Akya is in Brooklyn starting her second year of medical school this fall. Akya describes a commitment to serve as an honor, rather than a requirement, and she is excited to work with an underserved community as a gastroenterologist after residency.

Akya grew up in Brooklyn, New York, after her mother immigrated from Jamaica to secure better services for her son who is profoundly mentally disabled. Akya learned that while medical care was better in the United States, her mother and brother still struggled to access quality medicine and culturally competent care. This inequity led Akya to pursue a career in medicine but also drove her to serve vulnerable communities and individuals who are chronically underserved. After completing her post-bac degree at the AMSNY University at Buffalo program, Akya is in Brooklyn starting her second year of medical school this fall. Akya describes a commitment to serve as an honor, rather than a requirement, and she is excited to work with an underserved community as a gastroenterologist after residency. Before moving to the Bronx at age 11, Diana lived in the Dominican Republic and initially struggled to learn English when she came to New York. Through her parents’ urging, after graduating from her eighth grade English as a Second Language (ESL) program, she transitioned into a high school without an ESL program and had to quickly pick up the English language. While in high school, she participated in a summer internship at St. Vincent Medical Center’s Emergency Department. It was through this program that she gained a deeper understanding of how important it is for physicians to provide quality care and to help patients make better health choices. After college, Diana worked as a Perinatal Health Coordinator at the Institute for Family Health providing health education and guidance to low-income pregnant women. Diana says that growing up in the Bronx, one of the poorest counties in the country, leads her to view advocacy and justice as an obligation for healthcare professionals. Diana is starting her second year at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and looks forward to providing proactive healthcare to underserved areas.

Before moving to the Bronx at age 11, Diana lived in the Dominican Republic and initially struggled to learn English when she came to New York. Through her parents’ urging, after graduating from her eighth grade English as a Second Language (ESL) program, she transitioned into a high school without an ESL program and had to quickly pick up the English language. While in high school, she participated in a summer internship at St. Vincent Medical Center’s Emergency Department. It was through this program that she gained a deeper understanding of how important it is for physicians to provide quality care and to help patients make better health choices. After college, Diana worked as a Perinatal Health Coordinator at the Institute for Family Health providing health education and guidance to low-income pregnant women. Diana says that growing up in the Bronx, one of the poorest counties in the country, leads her to view advocacy and justice as an obligation for healthcare professionals. Diana is starting her second year at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and looks forward to providing proactive healthcare to underserved areas. Sebastian grew up in a single-parent home in Brooklyn, New York, where his mother continually sacrificed for his well-being and led him to develop a passion of putting others first at a young age. Throughout high school, he helped translate for his grandmother when she saw the doctor since her physician was not fluent in Haitian-Creole. Even with the language barrier, Sebastian recalls that the physician served as an advocate, healer, and teacher for his grandmother which led him to also pursue a career as a doctor. Sebastian looks forward to serving a medically underserved community because he grew up in one himself and feels it is his duty to return the service. Sebastian is starting his third year at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and has a long-term goal of establishing a health care center in an underserved area to offer holistic and culturally appropriate care.

Sebastian grew up in a single-parent home in Brooklyn, New York, where his mother continually sacrificed for his well-being and led him to develop a passion of putting others first at a young age. Throughout high school, he helped translate for his grandmother when she saw the doctor since her physician was not fluent in Haitian-Creole. Even with the language barrier, Sebastian recalls that the physician served as an advocate, healer, and teacher for his grandmother which led him to also pursue a career as a doctor. Sebastian looks forward to serving a medically underserved community because he grew up in one himself and feels it is his duty to return the service. Sebastian is starting his third year at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and has a long-term goal of establishing a health care center in an underserved area to offer holistic and culturally appropriate care. Nefertiti was raised in Harlem, New York, as the youngest of six siblings. At a young age, her family and many personal mentors in her community instilled strong values of education, hard work and perseverance, and a deep commitment to community empowerment. Her mother has been a nurse midwife in Harlem for over 30 years, which originally attracted Nefertiti to community- based healthcare. She is interested in medicine because it provides an opportunity for her to advocate for equity in social and health services that under- served communities lack. Nefertiti is passionate about solving systematic healthcare disparities by providing resources for access to mental health services in conjunction with physical health care. She is equally supportive of promoting primary care prevention, as a means to support the growth of more sustainable and healthy communities. She is currently in her third year at SUNY Upstate Medical University and plans to practice in a publicly funded hospital once she completes her training.

Nefertiti was raised in Harlem, New York, as the youngest of six siblings. At a young age, her family and many personal mentors in her community instilled strong values of education, hard work and perseverance, and a deep commitment to community empowerment. Her mother has been a nurse midwife in Harlem for over 30 years, which originally attracted Nefertiti to community- based healthcare. She is interested in medicine because it provides an opportunity for her to advocate for equity in social and health services that under- served communities lack. Nefertiti is passionate about solving systematic healthcare disparities by providing resources for access to mental health services in conjunction with physical health care. She is equally supportive of promoting primary care prevention, as a means to support the growth of more sustainable and healthy communities. She is currently in her third year at SUNY Upstate Medical University and plans to practice in a publicly funded hospital once she completes her training.