By JUSTIN O’CONNOR and SMRITI JACOB | February 20, 2025

Ryne Raffaelle spent much of last week in Washington, D.C. His mission, like that of university officials across the country, was to press lawmakers on the need to lift restrictions on National Institutes of Health research funding that the Trump administration is attempting to impose.

Then, Raffaelle, vice president of research at Rochester Institute of Technology, returned to Rochester to make a public plea alongside the University of Rochester.

The Trump administration’s sweeping actions on Feb. 7 turned to the NIH, the largest federal funder of biomedical research, with new policy guidance—a 15 percent cap on indirect research costs.

To some, these costs might seem excessive and justify a funding cap. Researchers and health policy advocates contend, however, that beyond halting research, the new limit could lead to job losses, lab closures, stalled career growth for young scientists and, most critically, a decline in the nation’s global technological edge.

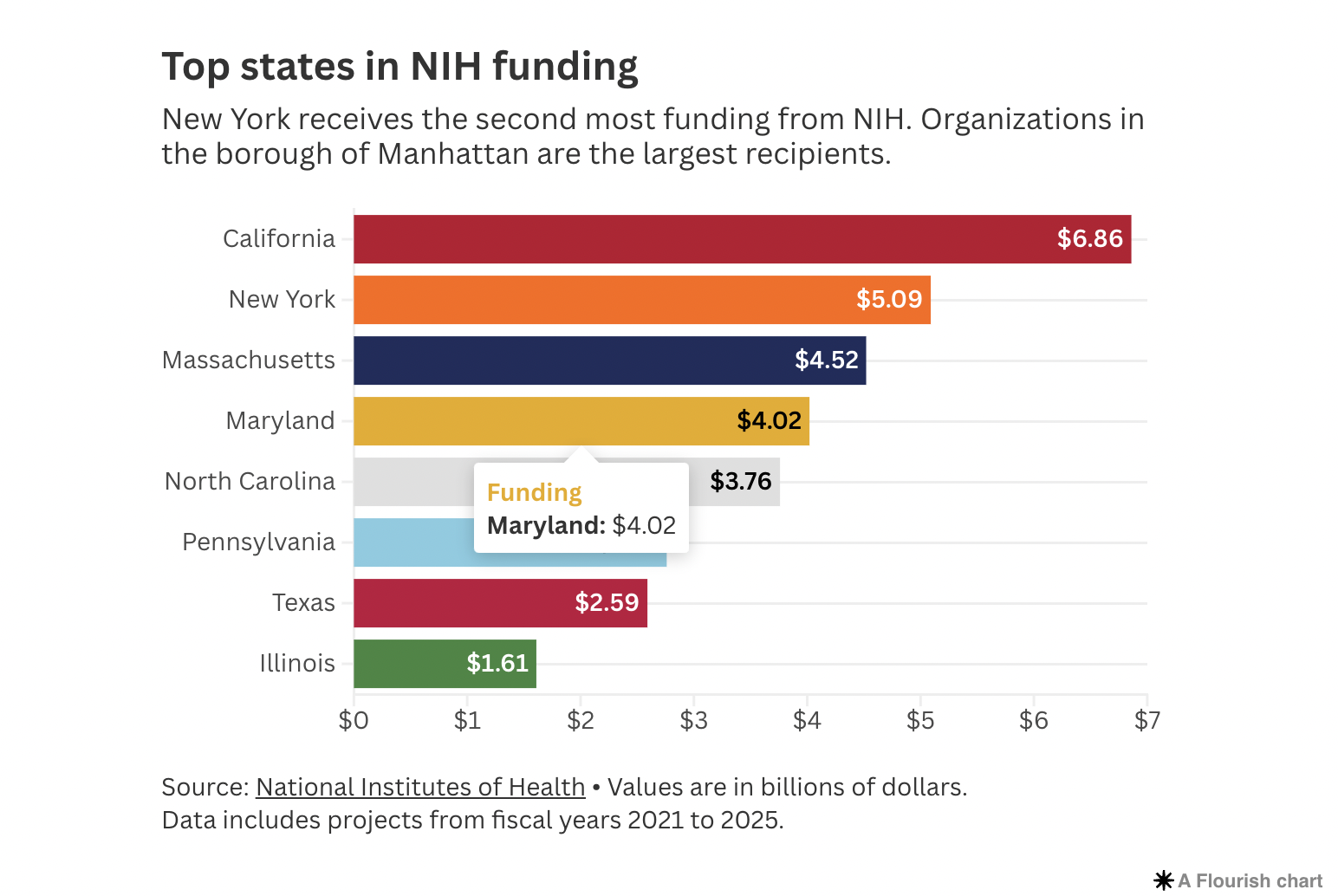

Jonathan Teyan, president and CEO of the Associated Medical Schools of New York, a consortium of 17 public and private medical schools, estimates a 15 percent cap would mean at least $630 million in lost NIH funding annually statewide. New York ranks second in NIH funds received, after California.

While attorneys general of 22 states and coalitions of universities have sued the Trump administration, there is concern that the ceiling on funding will hold. (A federal judge in Massachusetts temporarily blocked the NIH’s move.)

On Feb. 15, New York’s congressional delegation, including Rep. Joseph Morelle, signed a letter to Matthew Memoli M.D., NIH’s acting director, urging the agency to reconsider its policy change. The letter references an estimate from the Greater New York Hospital Association: an $850 million deficit due to the cap on indirect costs.

“The hope and the goal (is) that this will be rescinded, and that … hopefully there will be enough support in Congress and hopefully a recognition by the administration that this will actually have a really harmful effect on research,” Teyan says.

An attack on spending

The Trump administration’s decision on NIH funding is in line with its stated goal to slash federal spending. For researchers and scientists, it encroaches on an area that previously hasn’t been seen as a drain on federal dollars. Instead, scientific research has been viewed as a way for the U.S. to remain competitive globally.

Shortly after the policy change, national headlines echoed the outcry from research institutions and other advocates. Some went as far as to describe the new policy as “Science Under Siege” and an “‘Apocalypse’ for Science.”

The costs under scrutiny are a particular segment of NIH funding that includes facilities and administrative expenses (often called F&A or indirect costs) necessary to keep research going, including equipment maintenance, accounting and capital improvements required for a particular project.

Before the 15 percent cap, institutions negotiated a reimbursement rate for these costs in each grant. For instance, during the last fiscal year, UR had an average F&A reimbursement rate of 54 percent. The NIH says its average national F&A cost reimbursement hovers around 27 percent to 28 percent.

In rationalizing the cap, the NIH pointed to the reimbursement rates paid by private foundations that fund similar research, like the Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.

The Gates Foundation caps U.S. universities at a 10 percent indirect cost reimbursement rate, according to its indirect cost policy. The Rockefeller Foundation has a 20 percent reimbursement cap. The NIH identified them alongside seven other private grant funders with reimbursement caps around 15 percent.

“The United States should have the best medical research in the world. It is accordingly vital to ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead,” the agency said in justifying its move.

Many universities nationwide, however, contend that the funding cuts are a major threat to their ability to conduct research, and that the NIH’s rationale and legal foundation for the cap are misguided and illegal. Raffaelle, for instance, pushes back on the idea that F&A reimbursements are a profit boon for universities.

“Those overhead charges, those are sunk costs. It’s not like, I can suddenly take that overhead and just go throw it in the bank and (it) becomes a huge endowment,” Raffaelle says. “Endowments are given philanthropically.

“To somehow suggest that (overhead costs are) like profit that the university is making or salting away, it’s just ridiculous,” he adds. “That’s what I find pretty disturbing about this. These people don’t educate themselves. They don’t care to educate themselves when they come out with these wacky pronouncements that maybe it sounds plausible, but it’s anything but.”

In reality, Raffaelle says, universities lose money on research grants.

“There’s some cost-sharing that the university has to sort of engage in, because these overhead rates are negotiated with the federal government,” he says. “So, you negotiate—‘this is what all the real costs are’—and they tell you what you’re allowed to charge. And guess what? Although we negotiate real hard, we lose every time. The government always wins, so they always get the better of the deal.

“The reality is, we never recover all the costs expended, but the reason you do it is … for every grant you don’t want to (say), ‘OK, 25 cents for electricity, 50 cents for janitorial service.’”

Indeed, F&A spending includes many categories of expenses that are difficult to itemize on a grant-by-grant basis—like utilities, telecommunications, paperwork and sanitation costs, which can be complicated by a host of factors.

However, these line items aren’t trivial—they undergird all research. F&A spending includes measures for data security, regulatory compliance (including patient protections when human subjects are involved), and the handling of hazardous waste and dangerous substances, among other things.

“I read these statements by Elon Musk—the lack of understanding is kind of astonishing,” Raffaelle says. “Frankly, they don’t seem to realize what indirect costs or ‘overhead’ even is. They act like that’s some sort of a profit or some sort of a tax on the research that you’re doing. It’s not. That’s what covers all of the custodians and the electricity and the water, and those are real expenses associated with doing the work.”

These costs also don’t go unaudited. For example, NIH employees last fall visited UR to scan for compliance, and the university was notified one day before the 15 cap was announced that its average reimbursement rate would be cut modestly from 54 percent to 51 percent, UR president Sarah Mangelsdorf says.

Teyan says senior NIH-funded labs are often compared to small businesses within a medical school—they have to operate in a lean fashion to continue funding their work.

“These scientists are doing this work because they care about the work,” he says. “They really want to drive costs into advancing the science, and so they’re not padding to have great facilities for themselves, or for salaries, or anything like that. They’re really driving as much of their expenses into advancing the science.”

By putting at risk the operation of research laboratories, Mangelsdorf says, the “draconian” limit on F&A funding “is detrimental to the future health of all Americans, destabilizes the economic and technological innovation of the country, and puts in jeopardy the nation’s position as the scientific and clinical research leader of the world.”

Court battle

On Feb. 10, a U.S. District Court judge temporarily halted the cap in response to a case filed by 22 states against the NIH. That action is one of the major legal challenges against the move, with another coming from three higher education groups and 13 universities, including UR.

A significant issue in the case is the fact that the agency aims to apply the cap to existing grant agreements.

While the NIH claims to have the legal authority to do this as long as its new funding consideration process was spelled out publicly, the universities’ suit argues that the move is a flagrant violation of a repeatedly reenacted addition to Congress’ 2018 appropriations law that restrains the NIH from changing its approach to F&A reimbursements.

In its justification for the cap, the NIH made no mention of that appropriations rider, which is still in effect. It was passed after the Trump administration attempted to set a 10 percent cap on F&A reimbursements during his first term.

Raffaelle, too, rebukes the proposed changes to existing grant agreements.

“That’s illegal,” he says. “Never say never, but how could that possibly be executed? I don’t think that it would. But even saying things like that or trying to do something like that just creates tremendous turmoil.”

The schools and organizations also argue that there are numerous other ways that the move is in conflict with the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs how agencies issue regulations.

They also pushed back on the NIH’s use of private foundation grant terms as a benchmark. Private grants, they argue, often fund types of research different from those the NIH supports, and the grant terms are set with both parties presupposing federal funding.

The next hearing in the states’ case is set for Friday.

If the cap were allowed, the plaintiffs in the universities’ case say the effects would be catastrophic for research and the U.S.’s global scientific edge. UR says its reimbursements would be reduced by more than $40 million—over one-fifth of its total NIH funding.

“Even at larger, well-resourced institutions, this unlawful action will impose enormous harms, including on these institutions’ ability to contribute to medical and scientific breakthroughs,” the universities’ complaint contends. “Smaller institutions will fare even worse—faced with more unrecoverable costs on every dollar of grants funds received, many will not be able to sustain any research at all and could close entirely.”

High stakes

New York has long been a frontrunner in biomedical research funding. Last year, Teyan says, the state received $3.6 billion in NIH dollars.

RIT’s research report last fall noted it received $10 million from the NIH in fiscal 2024. The University of Rochester got $188 million, according to its public updates. Other organizations that received NIH funding include Rochester General Hospital, Litron Laboratories, Lightoptech Corp., Chess Mobile Health, and Urban Design 4 Health, according to NIH RePORTER.

“One of the other things that we frequently cite is how important each of the medical schools is as a sort of a nexus of a regional life sciences hub, and I think Rochester is a great example of that,” Teyan says. “The U of R is one of the major employers in the region, and has really been an anchor to the life sciences sector in Rochester, which has really grown in the (last) couple of decades.”

This research directly translates to jobs outside the academic realm. UR and RIT both have spun off startups employing several hundreds of people and working with domestic and international companies.

A high-profile illustration is the Prevnar vaccine, now known as the Hib vaccine, often lauded as a vital advancement in pediatric medicine. The vaccine was developed at UR, spun off into a startup, Praxis Biologics, which was later bought by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Other startup successes include Vaccinex, iCardiac Technologies and Casana.

“All of this is part of (a) coherent ecosystem,” Teyan observes. “So, NIH funding supports the basic science research, which (leads to) incubators and accelerators that help launch new companies from academia. All of this is part of that continuum. You don’t get new companies, you don’t get new life sciences products, without that basic science research.”

The Associated Medical Schools of New York points to the multiplier effect of NIH dollars in employment.

“Statewide, there are about 17,000 people directly employed in research,” Teyan says. “But outside of that, for each of those jobs, there’s about a 1.35 (jobs) multiplier effect. There are other people who are then employed in research-related activities, whether it’s people who are supplying materials or in the life sciences sector, people who are in startup companies or working in that sort of arena. There’s definitely that multiplier. And then there’s the kind of the spending multiplier as well.”

Nationwide, Teyan says, for every dollar in NIH funding, there’s an additional $2.4 in economic activity.

With cuts in funding, such downstream benefits might be reduced, experts warn. Then, there’s talent—universities are able to attract enterprising junior faculty because of the facilities on campus and the faculty’s interest in advancing science.

“We have junior faculty really worried right now,” Raffaelle says. “They’re hired with high research aspirations, and there’s things that they want to do as academics, as sponsored research principal investigators, and now they’re really worried. They’re like, ‘Hey, my career plans could be derailed by this kind of stuff.’ I’ve been trying to just calm them down.”

Lab closures loom on the horizon if these cuts go as planned, Teyan says. This could also affect budding researchers—labs working on cutting-edge research, cures and technologies often attract graduate students.

“It’s already difficult doing science because there is so much time that has to be spent on compliance and applying for grant funding, all of that. There’s not a lot of wiggle room here to cut additional expenses, it really will translate into less science getting done,” he adds. “Bigger picture, this will mean that some labs will have to close, and some people will end up getting laid off. I think that’s inevitable if this decision is not rescinded.”

Raffaelle also considers the nation’s competitive advantage. U.S. research prowess has given it a leg up in the global market.

“The fact that you don’t value education, or the people who don’t understand technological superiority, they obviously did not learn the lesson of World War II, says Raffaelle, referring to research efforts during that period that led to innovations like radar and jet propulsion and laid the groundwork for technological advancements. “It’s sad to think that that’s the case, but the people who would benefit the most (from) this are the (Chinese). This is like a dream come true for the Chinese.”

The universities’ lawsuit echoes his concerns.

“America’s rivals will cheer the decline in American leadership that the (NIH’s announcement) threatens,” the complaint reads. “But that decline should not occur—because well-established principles of constitutional and administrative law require setting the (new policy) aside.”

Justin O’Connor is a Rochester Beacon contributing writer. Smriti Jacob is managing editor. Contributing writer Jacob Schermerhorn created the data visualization.

The Beacon welcomes comments and letters from readers who adhere to our comment policy including use of their full, real name. See “Leave a Reply” below to discuss on this post. Comments of a general nature may be submitted to the Letters page by emailing Letters@RochesterBeacon.com.

Read the full article: https://rochesterbeacon.com/2025/02/20/a-direct-attack-on-research-funding/